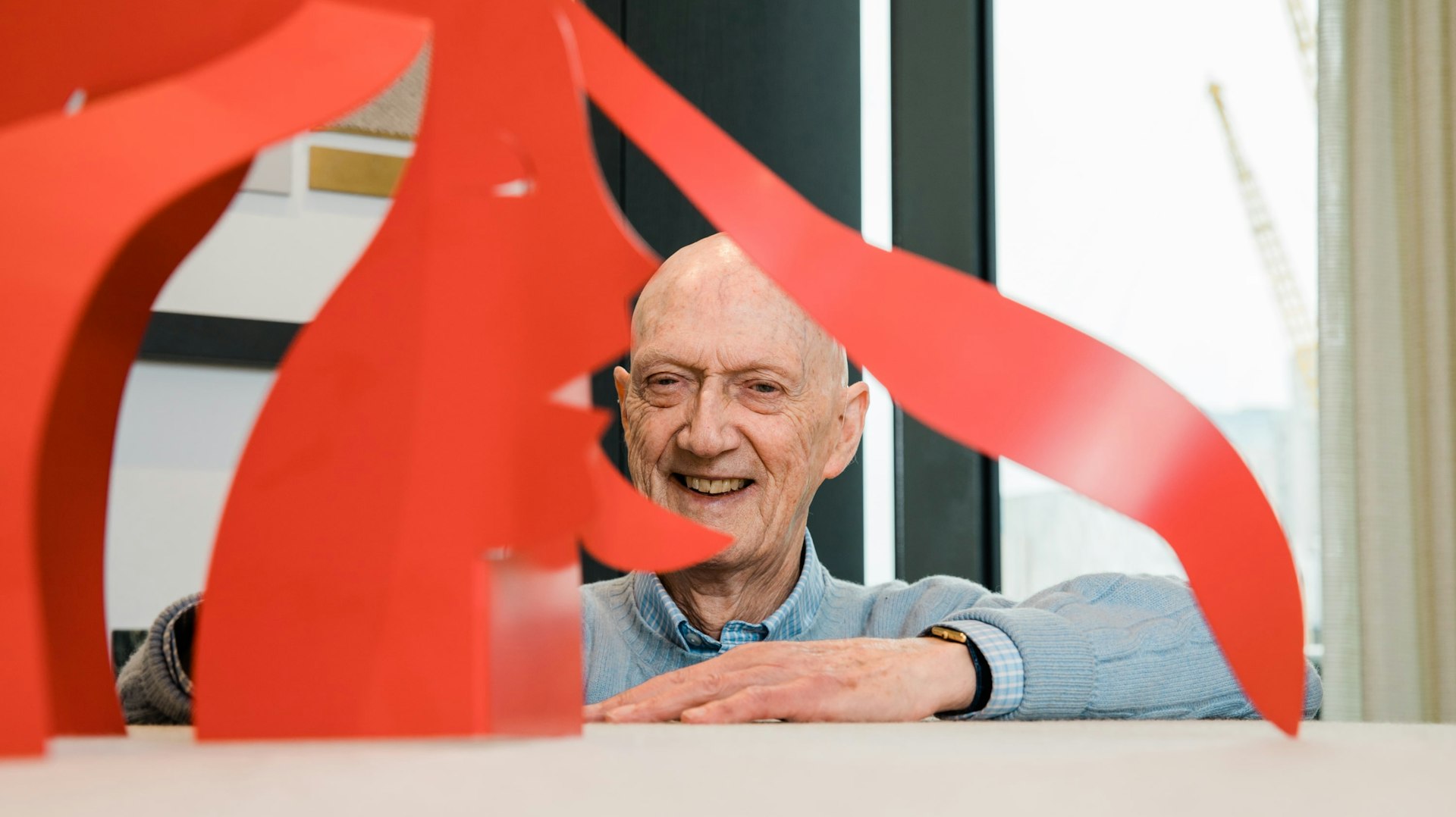

Allen Jones

There’s a nice circularity to Allen Jones’s new public artwork, Head in the Wind. That’s not just due to the beautiful, swooping locks of the silhouette’s head, but also because the work inadvertently shares its name with a much earlier piece by Jones, made 60 years earlier, back when he was a student in London. During the intervening decades, the artist has found fame as a British pop pioneer, won the admiration of fellow creatives such as the director Stanley Kubrick, and tried himself in another great art-world metropolis, New York. Read on to discover why he believes 'Head in the Wind' bookends his career.

The name of your new, large, public sculpture on Greenwich Peninsula, Head in the Wind, shares it's name with a very early picture you made at the Hornsey Art College. Could you tell us about that earlier work?

I recently found it by chance, I made it in 1959. It’s remarkable to see how it’s bookending my career, but it confirms something I’ve always believed: that is within everybody there is a notion of completeness, which is unconsciously operating. Anyway, you can see Picasso and [fellow cubist] Georges Braque in there. That’s the sort of stuff I was learning about at Hornsey Art College. There was one teacher of mine whose work looked as though it had been made in the 20th century, and I drew on that. I suppose I was learning about how subject needs a graphic presence. And I still like the picture now. I was amazed to see it, not least because of the title.

You not only went to college in London, you also grew up in the city. What are your earliest memories of the British Captial?

My family lived in west London, in Ealing. My first memories date from World War II. I remember the guns firing in the park, as they had an anti-aircraft emplacement there.

We also had two Canadian soldiers billeted in our house; I remember they would come off shift duty and leave their Enfield rifles in the hallway. Those guns were taller than I was. For birthdays and days out, we would go into the city, catching the underground, from Ealing Broadway to Marble Arch, where the city really began. It was a glamorous place. My parents also used to take me to museums. They weren’t very interested in the arts, but they realised I had a talent for drawing, so we would go to the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum.

“My parents also used to take me to museums. They weren’t very interested in the arts, but they realised I had a talent for drawing, so we would go to the science museum and the natural history museum.”

You moved to New York soon after graduating from college. How did that city compare with London?

It was fantastic. I had just got married, and we lived in the Chelsea Hotel. I can remember going ice skating in Central Park with the likes of Roy Lichtenstein. There was no doubt about it, New York was the centre of the art world back then. Going to New York was important, because it was the place where you could test yourself. I think that the European tradition from the Renaissance onwards didn’t sit so heavily on them. They didn’t have that weight of seeing the world in that way.

Later, you got to know one famous New Yorker, Stanley Kubrick, when he tried to commission your works for his film, A Clockwork Orange.

Yes. I never met Kubrick face-to-face, but we spoke on the phone. He’d seen an exhibition of mine [featuring sculptures of women worked into tables and chairs] and he asked if he could use the sculptures in his new movie. I took advice and I was told they’d get trashed. I offered to design something for them, but that didn’t work out; basically, he thought I’d do the work for a credit, but no monetary fee. However, I gave him my blessing to use the idea. I mean you can’t copyright an idea, can you? The strange thing is, a few years later, my gallery received a call from Gianni Agnelli [the head of Fiat], saying he was interested in one of my table sculptures. I said we didn’t have any. He said, ‘Oh no, the white ones’ and that he’d seen them in the Italian film studios, Cinecittà. Well, I never made any white ones, so he must have come across the old Clockwork Orange props.

So your latest artwork is on a new piece of London, on Greenwich Peninsula. Tell us more.

The primary thing about the Head in the Wind location is that some people would have to live with it outside their apartment or office window, whereas for the passer-by might catch just a fleeting glance. To have something that would have some meaning from a distance helped establish the work’s size. Also, you have to let these pieces go eventually, too. I made a pair of 4m-high works for a street in Hong Kong. At this moment, the developers have pulled the buildings down and they’re extending the street. They’ve contacted me to ask if they can change the colours of the works. It’s odd to have these kinds of discussions about something you’ve worked very hard on; but if they want to paint them yellow, they can paint them yellow. I think the colour change, like the Peninsula, won’t violate the piece. Artworks can be a bit like children; they’re yours, but they grow up and become their own entities.

“Artworks can be a bit like children; they’re yours, but they grow up and become their own entities.”