The Design District London

London: capital of Great Britain and, some would argue, of creativity. A city whose history is layered with daring invention and innovation in every possible sector. Its timeless appeal to thinkers, makers and creators has seen it become the birthplace of every kind of creative output. Its openness is legendary, its diversity unmatched. The effect is circular: because it inspires so many, the yield of their efforts reinvents and reinvigorates the city to carry on being inspiring.

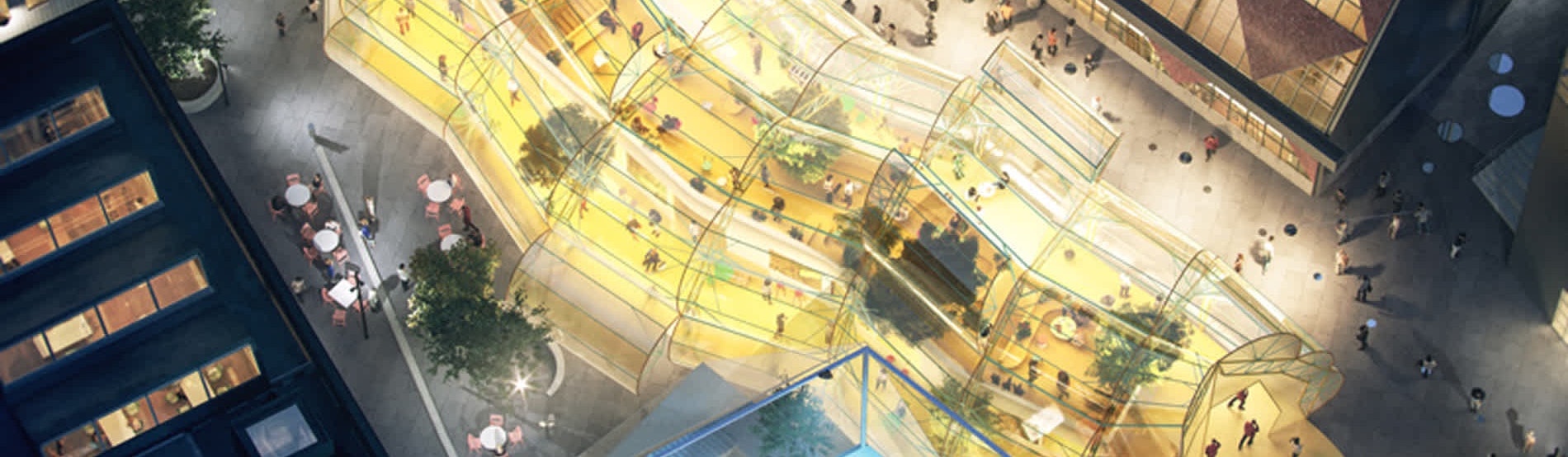

And the creators keep on flocking to London’s open arms. The milliner hunched over her block, the writer pen in hand, the architect who looks to the skyline and sees a different future; all need space to create. Vision and brilliance are all very well, but there are practicalities too—dependable investment, affordable rent, physical spaces for large canvasses, places you can make dirty. However, rising costs, for too long, have driven both the solo artist and larger scale creative enterprise into the suburbs and beyond. Even the studio spaces that evolve and grow out of unwanted or disused buildings are becoming harder to find. But now a dedicated place is rising from the ground up. The Design District on Greenwich Peninsula, opening in 2019, is London’s first purpose-built district made specifically for the creative community.

It’s a place of idea incubation, seeding and pollination. A destination that will keep thinkers, makers and doers in the very place that brings their ideas to life. Fixed and subsidised rents across the district will make this an affordable base for those drawn here – 1,500 individuals to be exact, working across 150,000 square foot of studio, workshop and desk space. And there will be all important room to play too: markets, a basketball pitch, public galleries and walkways enabling locals and visitors alike to mingle, merge and explore.

The key to the Design District’s success, however, will lie in its ability to be what it says it is: a district. A creative neighbourhood; a distinct community rising from the sparks of creatives at work. Its biggest challenge will be to build and feed the fires of collaboration and entrepreneurship.

“"Cities and communities now realise they have to attract and retain the creative talent needed to drive their cities forward. [they] have to be brain-gain places and not brain-drain."”

“– Richard Florida, urban studies theorist and author of The Rise of the Creative Class.”

“London’s going through a thing at the moment where so much is relentlessly commoditized and every square inch of space is monetised. What T.S. Eliot called the ‘necessary laziness’ of poets is in danger of disappearing. The Design District will be buzzing, but it will also be flexible, enjoyably odd and somewhat dysfunctional in parts.” says Peter Besley, co-founder of architect firm, Assemblage, the masterplanners of the Design District.

Hannah Corlett, Assemblage’s co-founder adds: “This isn’t a cynical ‘pop up’, it will support and provide succour, and hopefully inspire others to do the same. Then it’s over to the artists.”

Occupying the space between Dome and park, the Design District is a stake in the ground for London’s disparate and diverse creative communities, over which hangs a big ‘welcome’ sign for all those who enjoy their output. It’s a long-term investment in grassroots creativity. A place where mixers, woodworkers, thinkers, planners, laptoppers, drawers of art can overlap in the most organic and public of networks. Everyone is invited.

“"It should feel like quite a distinct little neighbourhood, rather than a co-working business district."”

“– Matthew Dearlove, Greenwich Peninsula’s Head of Design”

“It should feel like quite a distinct little neighbourhood, rather than a co-working business district,” says Matthew Dearlove, Greenwich Peninsula’s Head of Design. “A neighbourhood”, he stresses, “that belongs as much to the Peninsula pioneer on her morning commute or the Londoner absconding from his usual pocket of the city, as it does the rent-paying jeweller, potter or composer. The area provides real activity at street level, an interesting place to walk or just hang out— there’s a food market with room for up to 20 stalls, two cafes, and in the ground floors of each building workshops spill out onto courtyards, creating opportunities for shops and galleries to spring up for the public to explore their wares.”

There is an undeniable affection for the numerous pouches of London that have played the role of creative hub since the city’s beginnings: the cobbled mews of Bloomsbury, the narrow streets of Soho, the scrappy warehouse conversions of Shoreditch. All multifunctional, all offering the kind of temporariness befitting the ever-changing worlds of design, art, fashion, music, food and digital whose champions pass through. But the Design District is here to stay.

“"We want the design district to be active, for diversity and change to allow the neighbourhood to evolve. But all the while, they occupy a lasting structure. So, parts might start out as quite an arty space, then over time it could shift into music or film or something else. Ebb and flow is part of what gives it its permanence."”

“– Matthew Dearlove”

There’s a purposefulness to it that brings a permanence that’s at odds with the idea of small-scale craftspeople and start-up studios, of design trends themselves even. “There’s a dynamic turnover in the type of tenant mix we’re thinking about,” says Dearlove. “Someone working with leather, a small graphic design business, a local jeweller…yes, there’s a transience to that type of business model. We welcome that turnover because we want the Design District to be active, for diversity and change to allow the neighbourhood to evolve. But all the while, they occupy a lasting structure. So, parts might start out as quite an arty space, then over time it could shift into music or film or something else. Ebb and flow is part of what gives it its permanence.”

Space for spontaneity is something encouraged in the district’s design. Eight pairs of buildings have each been given to separate London and European-based architectural firms, all with their own unique aesthetic. They’ve been asked to work blind, ensuring no ‘corporate’ voice or overarching idea can creep into a space conceived to be the very opposite. Its creators wanted the district to look and feel as unique as its occupants.

“When designers work too closely together, group-think can find its way into what people are doing,” Dearlove explains. “We wanted each architect to be independent and come to the project with their own original ideas. The result is a slightly cacophonous language—it’s fun, different, vibrant and slightly Marmite in that some will love a building; others will hate it. But that’s ok, because that’s what happens in cities.” The path to creativity is uncharted territory. There is no map to follow on the journey to ideas, no ‘suggested route’ or rulebook. The same can be said for the visitor coming to the Design District. There’s roaming to be done for sure, and there’s things to be seen in the spaces between buildings, tucked away in corners, hidden in courtyards and in the workshops lining the streets. “Being enjoyably lost on occasion is important. So is discovering things you had no idea were there. We think people will really embrace it,” says Cortlett.

So the Design District belongs entirely and democratically as much to Londoners as it does the creatives who work here. But it is the latter who will really own this space entirely, infuse it with their ideas, their experiments, their mess, their joy, their will, their way. It’s in this freedom that the future begins, where the embryos of the next big thing may come to be. Whatever ingenuity there’ll be between the people and the buildings, it’s for them to decide.

For more information click here.

“"Being enjoyably lost on occasion is important. So is discovering things you had no idea were there. We think people will really embrace it."”

“– Cortlett”